Welcome to Visit Weald Places

The Walkfo guide to things to do & explore in Weald

![]() Visit Weald places using Walkfo for free guided tours of the best Weald places to visit. A unique way to experience Weald’s places, Walkfo allows you to explore Weald as you would a museum or art gallery with audio guides.

Visit Weald places using Walkfo for free guided tours of the best Weald places to visit. A unique way to experience Weald’s places, Walkfo allows you to explore Weald as you would a museum or art gallery with audio guides.

Visiting Weald Walkfo Preview

The Weald is an area of South East England between the parallel chalk escarpments of the North and the South Downs. It crosses the counties of Hampshire, Surrey, Sussex and Kent. It has three separate parts: the sandstone “High Weald” in the centre, the clay “Low Weald”, the clay Weald periphery and the Greensand Ridge. When you visit Weald, Walkfo brings Weald places to life as you travel by foot, bike, bus or car with a mobile phone & headphones.

Weald Places Overview: History, Culture & Facts about Weald

Visit Weald – Walkfo’s stats for the places to visit

With 3 audio plaques & Weald places for you to explore in the Weald area, Walkfo is the world’s largest heritage & history digital plaque provider. The AI continually learns & refines facts about the best Weald places to visit from travel & tourism authorities (like Wikipedia), converting history into an interactive audio experience.

Weald history

Prehistoric evidence suggests that, following the Mesolithic hunter-gatherers, the Neolithic inhabitants had turned to farming, with the resultant clearance of the forest. With the Iron Age came the first use of the Weald as an industrial area. Wealden sandstones contain ironstone, and with the additional presence of large amounts of timber for making charcoal for fuel, the area was the centre of the Wealden iron industry from then, through the Roman times, until the last forge was closed in 1813. The index to the Ordnance Survey Map of Roman Britain lists 33 iron mines; and 67% of these are in the Weald. The entire Weald was originally heavily forested. According to the 9th-century Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, the Weald measured 120 miles (193 km) or longer by 30 miles (48 km) in the Saxon era, stretching from Lympne, near Romney Marsh in Kent, to the Forest of Bere or even the New Forest in Hampshire. The area was sparsely inhabited and inhospitable, being used mainly as a resource by people living on its fringes, much as in other places in Britain such as Dartmoor, the Fens and the Forest of Arden. The Weald was used for centuries, possibly since the Iron Age, for transhumance of animals along droveways in the summer months. Over the centuries, deforestation for the shipbuilding, charcoal, forest glass, and brickmaking industries has left the Low Weald with only remnants of that woodland cover. While most of the Weald was used for transhumance by communities at the edge of the Weald, several parts of the forest on the higher ridges in the interior seem to have been used for hunting by the kings of Sussex. The pattern of droveways which occurs across the rest of the Weald is absent from these areas. These areas include St Leonard’s Forest, Worth Forest, Ashdown Forest and Dallington Forest. The forests of the Weald were often used as a place of refuge and sanctuary. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle relates events during the Anglo-Saxon conquest of Sussex when the native Britons (whom the Anglo-Saxons called Welsh) were driven from the coastal towns into the recesses of the forest for sanctuary,: A.D. 477. This year came Ælle to Britain, with his three sons, Cymen, and Wlenking, and Cissa, in three ships; landing at a place that is called Cymenshore. There they slew many of the Welsh; and some in flight they drove into the wood that is called Andred’sley. Until the Late Middle Ages the forest was a notorious hiding place for bandits, highwaymen and outlaws. Settlements on the Weald are widely scattered. Villages evolved from small settlements in the woods, typically four to five miles (six to eight kilometres) apart; close enough to be an easy walk but not so close as to encourage unnecessary intrusion. Few of the settlements are mentioned in the Domesday Book; however Goudhurst’s church dates from the early 12th century or before and Wadhurst was big enough by the mid-13th century to be granted a royal charter permitting a market to be held. Before then, the Weald was used as summer grazing land, particularly for pannage by inhabitants of the surrounding areas. Many places within the Weald have retained names from this time, linking them to the original communities by the addition of the suffix “-den”: for example, Tenterden was the area used by the people of Thanet. Permanent settlements in much of the Weald developed much later than in other parts of lowland Britain, although there were as many as one hundred furnaces and forges operating by the later 16th century, employing large numbers of people. In the 12th century, the Weald still extended so far that citizens of London could hunt wild bull and the boar in Hampstead. Even during the more modern Plantagenet era, it was said that “a squirrel might leap from tree to tree for nearly the whole length of Warwickshire.” In 1216 during the First Barons’ War, a guerilla force of archers from the Weald, led by William of Cassingham (nicknamed Willikin of the Weald), ambushed the French occupying army led by Prince Louis near Lewes and drove them to the coast at Winchelsea. The timely arrival of a French Fleet allowed the French forces to narrowly escape starvation. William was later granted a pension from the crown and made warden of the Weald in reward for his services. In the first edition of On The Origin of Species, Charles Darwin used an estimate for the erosion of the chalk, sandstone and clay strata of the Weald in his theory of natural selection. Charles Darwin was a follower of Lyell’s theory of uniformitarianism and decided to expand upon Lyell’s theory with a quantitative estimate to determine if there was enough time in the history of the Earth to uphold his principles of evolution. He assumed the rate of erosion was around one inch per century and calculated the age of the Weald at around 300 million years. Were that true, he reasoned, the Earth itself must be much older. In 1862, William Thomson (later Lord Kelvin) published a paper “On the age of the sun’s heat”, in which – unaware of the process of solar fusion – he calculated the Sun had been burning for less than a million years, and put the outside limit of the age of the Earth at 200 million years. Based on these estimates he denounced Darwin’s geological estimates as imprecise. Darwin saw Lord Kelvin’s calculation as one of the most serious criticisms to his theory and removed his calculations on the Weald from the third edition of On the Origin of Species. Modern chronostratigraphy shows that the Weald Clays were laid down around 130 million years ago in the Early Cretaceous.

Weald culture & places

The Weald has been associated with many writers, particularly in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Vita Sackville-West (1892–1962), Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (1859-1930) and Rudyard Kipling (1865–1936) The setting for A.A. Milne’s Winnie-the-Pooh stories was inspired by Ashdown Forest.

Weald etymology

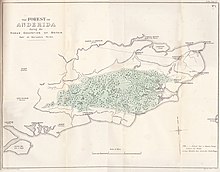

Weald is a West Saxon form; wold is the Anglian form of the word. In early medieval Britain, the area had the name Andredes weald, meaning “the forest of Andred”, the latter derived from Anderida, the Roman name of present-day Pevensey. Middle English form of word is wēld, and the modern spelling is a reintroduction of the Old English form.

Weald geography / climate

The Weald begins north-east of Petersfield in Hampshire and extends across Surrey and Kent in the north, and Sussex in the south. In extent it covers about 85 miles (137 km) from west to east, and about 30 miles from north to south, covering an area of 500 square miles (1,300 km) The eastern end of the High Weald is marked in the centre by the high sandstone cliffs from Hastings to Pett Level.

Why visit Weald with Walkfo Travel Guide App?

![]() You can visit Weald places with Walkfo Weald to hear history at Weald’s places whilst walking around using the free digital tour app. Walkfo Weald has 3 places to visit in our interactive Weald map, with amazing history, culture & travel facts you can explore the same way you would at a museum or art gallery with information audio headset. With Walkfo, you can travel by foot, bike or bus throughout Weald, being in the moment, without digital distraction or limits to a specific walking route. Our historic audio walks, National Trust interactive audio experiences, digital tour guides for English Heritage locations are available at Weald places, with a AI tour guide to help you get the best from a visit to Weald & the surrounding areas.

You can visit Weald places with Walkfo Weald to hear history at Weald’s places whilst walking around using the free digital tour app. Walkfo Weald has 3 places to visit in our interactive Weald map, with amazing history, culture & travel facts you can explore the same way you would at a museum or art gallery with information audio headset. With Walkfo, you can travel by foot, bike or bus throughout Weald, being in the moment, without digital distraction or limits to a specific walking route. Our historic audio walks, National Trust interactive audio experiences, digital tour guides for English Heritage locations are available at Weald places, with a AI tour guide to help you get the best from a visit to Weald & the surrounding areas.

“Curated content for millions of locations across the UK, with 3 audio facts unique to Weald places in an interactive Weald map you can explore.”

Walkfo: Visit Weald Places Map

3 tourist, history, culture & geography spots

Weald historic spots | Weald tourist destinations | Weald plaques | Weald geographic features |

| Walkfo Weald tourism map key: places to see & visit like National Trust sites, Blue Plaques, English Heritage locations & top tourist destinations in Weald | |||

Best Weald places to visit

Weald has places to explore by foot, bike or bus. Below are a selection of the varied Weald’s destinations you can visit with additional content available at the Walkfo Weald’s information audio spots:

| Bateman’s Bateman’s is a 17th-century house located in Burwash, East Sussex. It was the home of Rudyard Kipling from 1902 until his death in 1936. Kipling’s widow Caroline bequeathed the house to the National Trust in 1939. |

Visit Weald plaques

![]() 1

1

plaques

here Weald has 1 physical plaques in tourist plaque schemes for you to explore via Walkfo Weald plaques audio map when visiting. Plaques like National Heritage’s “Blue Plaques” provide visual geo-markers to highlight points-of-interest at the places where they happened – and Walkfo’s AI has researched additional, deeper content when you visit Weald using the app. Experience the history of a location when Walkfo local tourist guide app triggers audio close to each Weald plaque. Explore Plaques & History has a complete list of Hartlepool’s plaques & Hartlepool history plaque map.